A Clear and Present Danger

About 9 years ago, John Hopkins University conducted an asthma study. During this study, a healthy, young volunteer named Ellen Roche died as a result of inhaling a chemical called hexamethonium. According to the Baltimore Sun, this story became more controversial when researchers discovered that there were several articles readily available online that described extremely serious side effects associated with this chemical, including death. Dr. Alkis Togias, the supervising physician, believed he did his due diligence by searching through medical textbooks as well as a commonly used and well-respected medical research database called PubMed. Tragically, however, these resources did not reveal results for the most critical and relevant studies about hexamethonium.

This deadly informational blind spot that was exposed by Roche’s death can ironically be associated with one of the criteria that John Hopkin’s own library website provides for evaluating online information. This relevant criterion is called “currency” or “the timeliness of information” and actually in this case, we are essentially talking about the opposite of currency. PubMed, at least at that time, only tracked articles back to 1960. Unfortunately, the research articles that could have provided Dr. Togias the crucial warnings about hexamethonium were all published during the 1950s.

To Google or Not to Google. That is the Question!

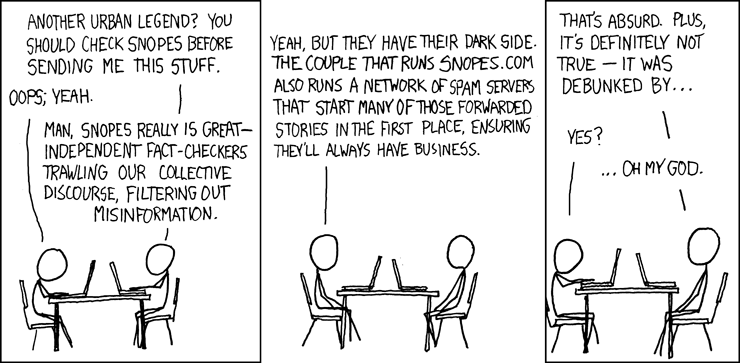

The sad story of Ellen Roche is an important case study that reveals a growing problem with the internet in general. As exciting, useful, and broad-reaching as Google’s search technologies appear to be, there is also a considerable risk and downside to their success. Google has generated a pervasive and problematic expectation or illusion among users that they truly do “provide access to the world’s information in one click.” Casual internet users, including many students and professionals, have gradually been seduced into believing that Google offers simple and immediate access to ALL the world’s information. “Mommy” blogger, “Christy” exclaims:

The sad story of Ellen Roche is an important case study that reveals a growing problem with the internet in general. As exciting, useful, and broad-reaching as Google’s search technologies appear to be, there is also a considerable risk and downside to their success. Google has generated a pervasive and problematic expectation or illusion among users that they truly do “provide access to the world’s information in one click.” Casual internet users, including many students and professionals, have gradually been seduced into believing that Google offers simple and immediate access to ALL the world’s information. “Mommy” blogger, “Christy” exclaims:“Oh, dear. The day has come where people honestly believe that if you can’t find it on Wikipedia or Google, it doesn’t exist.”It is quite possible that "Christie" may be right!

Searching With My Good Eye Closed

As amateur users increasingly adopt such attitudes about Google and overestimate their own searching abilities, they may fail to recognize the importance of using multiple database sources. Such users might also lose appreciation for information science professionals, such as librarians. In an Information Today article discussing the Roche case at John Hopkins, Eva Perkins states:

“Professional searchers — in this case, medical librarians — apparently have not made the potential and actual value of their contribution to the quality of searches visible enough to their clients for the clients to recognize the risks of working without them. Physician researchers overestimated their effectiveness as literature searchers and didn't compensate for any defects in their searching abilities by using professional networking to double- and triple-check their research. Database producers failed to build files and interfaces that would have found the needed information.”Perkins proceeds by putting pressure on both specialized and common search engine companies to do their best to actually meet the expectations of amateur users by building more usable graphical interfaces and better databases that communicate with other search engines in order to link (patch) the critical information gaps that currently exist between them.

I recently helped conduct a usability field study for a company called Stat!Ref that provides healthcare-related electronic resources as well as a robust search engine which indexes all of their materials. In this study, we interviewed 15 users who worked and/or studied at various hospitals and universities in Boston, MA and Portland, OR. Our user group represented a broad range of searching skills and included medical students, researchers, and librarians. In this study, we discovered that even the most advanced, highly-trained searchers were frustrated by information being too siloed as well as the lack of quality tools for sharing and collaborating during cooperative digital search activities. They also reiterated the challenge illustrated in the Roche case of gathering the most relevant and accurate information on topics that have been around for many decades.

Dig Deeper

The lack of access and awareness bias will continue to be a major challenge for information professionals and computer scientists. As more and more of our information is exclusively accessed via digital mediums and the technological expectations of users continues to rise, new tools will need to be developed in order to combat this hidden bias. According to Read Write Web,

“Less than 0.2% of the web is indexed and some of the most valuable information lies beyond search results returned from traditional search engines.”Fortunately, progress is being made as we speak. For example, an exciting new service called DeepDyve (formerly Infovell) was recently launched, promising search technology that “enables an untrained searcher to express complex concepts in a simple and intuitive way and provides easy-to-use tools for filtering and sorting through relevant and related documents.”

A Compact Digital World

User perceptions of traditional media are rapidly changing and evolving. For instance, in our Stat!Ref study, we learned that many students today have a hard time even describing the difference between a book and a scientific journal. Young students now rely heavily on digital versions of publications, and thus they have trouble conceptually understanding delineations that made perfect sense to those of us who are accustomed to physical, print versions of these publications. In the physical world, books have a considerably different look and feel than journal articles, but online, such tangible properties sort of fade into the background and readers are simply left with words on a screen.

As scientific communications continue to migrate to the internet and become intricately mixed together with other forms of communications (blogs, forums, e-books, video, etc.), researchers must also adopt new media strategies for effectively and credibly disseminating their important findings and analysis. Kenneth Goldsmith, a well-respected American poet and conceptual artist, is a big advocate of “academic blogging”. He believes that blogging generates “peer-based consensus” which in turn “garners credibility”. Goldsmith recognizes that blogging not only exposes research to the general public much earlier, but it also allows one to lay claim to research ideas before formally publishing them. Furthermore, it gives the academic researcher the opportunity to immediately engage in debate with others in their field, in real-time, about the validity of their methodology, results and interpretations.

These types of emerging social media interactions could definitely be interesting topics for us as media psychologists. Overall, I have learned that the most dangerous online biases may not necessarily be those that are found inside relevant online information but rather those that emerge from never finding the most relevant information at all.